A comparison between open source host firmware solutions and closed source UEFI

Table of Contents

This whitepaper makes the case that UEFI firmware and more specifically EDK2 based solutions, be it open or the more ubiquitous closed ones, hurt business by driving up cost and delaying time to market, while at the same time are the root cause of more and more security problems. This whitepaper will contrast this UEFI status quo with other existing solutions like LinuxBoot in combination with coreboot, which fully embrace open source development, are scoring better on all those metrics. This is both due to design decisions and the related development models.

To make this case it is first necessary to untangle the notion of host firmware. Everything that resides in the host flash boot medium is called host firmware. Silicon designs got more complicated and more integrated so naturally more and more firmware components are currently being placed in that host firmware flash. While the case for open source could likely be made for all the components on that flash, the focus of this whitepaper will be on the firmware that is run on the main CPU. On x86 systems a big part of silicon initialization is happening in that code. It’s good to further differentiate this into silicon specific hardware initialization and more generic hardware initialization and drivers that are used to load an operating system be it from disk or network. This roughly matches the UEFI PEI phase (silicon specific init) and UEFI DXE phase (load OS phase).

Part 1: UEFI DXE vs LinuxBoot

The DXE Foundation produces a set of Boot Services, Runtime Services, and DXE Services. The DXE Dispatcher is responsible for discovering and executing DXE drivers in the correct order. The DXE drivers are responsible for initializing the processor, chipset, and platform components as well as providing software abstractions for system services, console devices, and boot devices. These components work together to initialize the platform and provide the services required to boot an operating system. The DXE phase and Boot Device Selection (BDS) phases work together to establish consoles and attempt the booting of operating systems. The DXE phase is terminated when an operating system is successfully booted.

This is quoted from the UEFI PI spec 1.8. This basically sounds like UEFI DXE, Driver eXecution Environment, is an application specific operating system, with the application being loading an operating system. If that sounds like too many operating systems to you, then that’s what the project of LinuxBoot is all about: not reinventing the wheel. The idea is that most of what UEFI DXE phase is doing, Linux as a bootloader can do as well and typically better, be it faster and with less problems. So what the typical LinuxBoot firmware looks like and how does it work? LinuxBoot contains a small Linux kernel that is often very reusable on different hardware. It’s very common to have it just work on the first try. If necessary hardware specific kernel drivers can be added. This is then coupled with an initramfs that contains a small user space that is enough to securely load the target operating system, via kexec. Other functionality to debug or validate the platforms are often included in the initramfs too. A popular implementation of this initramfs is u-root . U-root is an initramfs builder, written in golang to create a busybox-like (1 binary) environment. Adding new commands and components is trivially achieved, which makes u-root very easy to customize.

So what are the advantages of this approach over UEFI DXE:

- The Linux kernel is really high quality battle tested and the code is under a lot of scrutiny due to the high number of contributors. Hitting problems on never tested UEFI DXE code and corner cases on the other hand is not uncommon.

- The target operating system is Linux, so using the same code and drivers in the bootloader, reduces development time.

- There are a lot more developers that can write Linux userspace applications than there are UEFI developers. UEFI is written in DOS style C, where Linux applications can be written in any modern language.

- Boot times are better as the Linux boot process is much better parallelized and is smarter at dependency resolution (UEFI often needs to reload DXEs).

- Much less programs are used: 1 kernel (kernel modules are built in) + 1 busybox userspace application vs sometimes 100s of DXE modules in UEFI. This makes the SBOM and therefore also maintenance of security updates much more manageable.

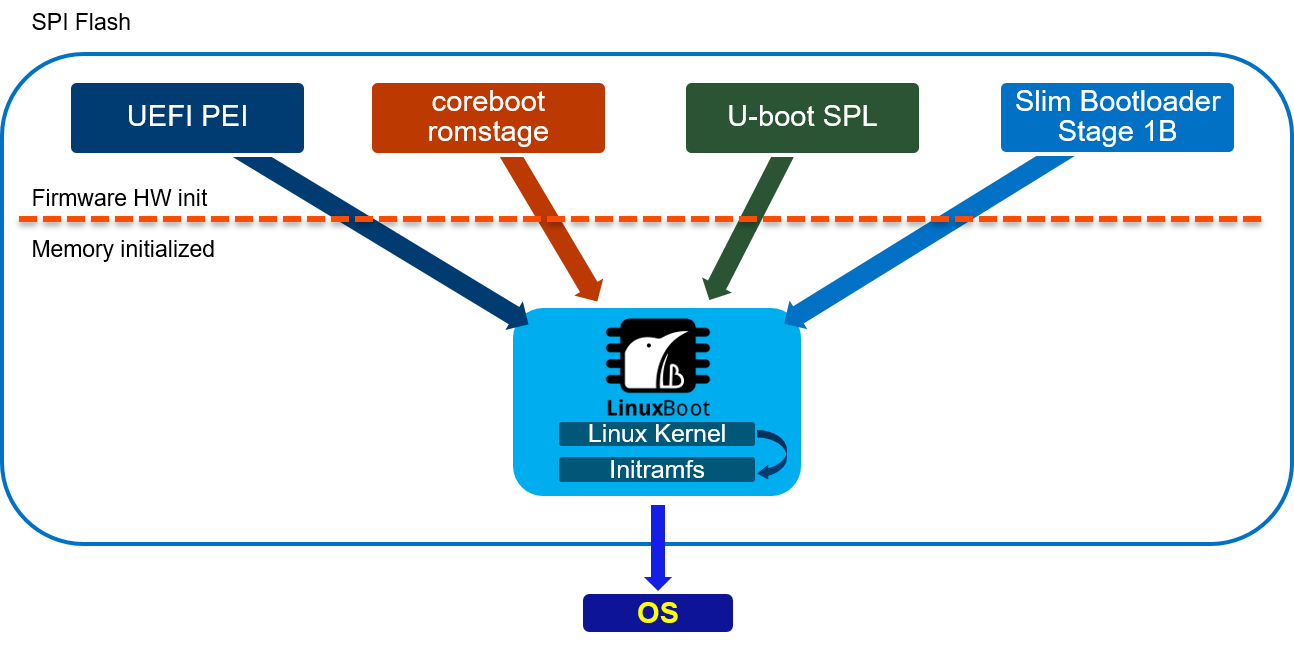

- It’s a very flexible bootloader that can be coupled with all sorts of hardware specific initializations: UEFI PEI, coreboot, u-boot, slim bootloader have all been successfully coupled.

LinuxBoot really isn’t a newcomer to the scene and is widely deployed in production for instance at Google and Bytedance. Some hardware vendors commonly use LinuxBoot to validate the hardware before implementing the UEFI firmware that eventually ships as it’s just that much easier/faster to get working.

Part 2: UEFI PEI & DXE vs coreboot

UEFI PEI, Pre-Efi Initialization, is in charge of doing silicon specific initialization before the DXE phase. This often consists of initialization of main memory (DRAM) amongst other things. It follows a similar modular design as the DXE phase:

- PEI Modules in charge of initialization of some part of the hardware

- A table of services that PEIM can use, e.g. heap services, multiple image support, …

- PEIM to PEIM Interfaces (PPI) services over which modules can talk to each other

- A instruction set for module dependency resolution

- Creating Hand of Blocks for the remaining of the boot (DXE)

This again sounds like an Operating System environment like DXE, but a bit more limited as main memory is not yet available. After main memory is installed and ready, UEFI moves on to DXE phase to do the rest of hardware initialization and loading of the OS happens. DXE is a richer environment as the availability of main memory implies less restrictions.

Coreboot is a open source firmware component that can be compared to the hardware init parts of UEFI PEI & DXE. It does not implement any loading of the OS, but loads a payload, which can be any kind of binary, to do this. The limited scope of coreboot makes it flexible with regards to the use cases as the hardware init part typically does not vary so much: e.g. whether a board is to be used as a highly embedded router or a laptop, the DRAM init part is identical. The payload is then specifically tailored to the use case. For instance on embedded systems like routers there is no use case for being able to run Windows, so there is no need for a fully fledged UEFI interface in the firmware. More on that topic in part 3. Datacenter servers are in many respects very similar to embedded systems even though compute power is dramatically higher. Datacenter servers all come in identical or at least with very little variation in their setup and they only need to boot Linux. Given this highly specific use case using LinuxBoot makes a lot of sense, be it with UEFI or coreboot.

Coreboot ‘s design is radically simpler than UEFI PEI + DXE. Coreboot does not follow a modular design: there is just 1 program running before DRAM is up (romstage) and 1 program after DRAM is ready (ramstage). This reduces the complexity of the code that needs to be run at runtime, by moving more logic at build time. This significantly reduces the size of the binary produced: there is simply less code (no dispatch, no services, no PPI) but also less compiled code to be duplicated, compared to PEI/DXE modules that need to reimplement certain features like a standard library in each module. Also the ‘1 binary’ approach makes optimizations like linker garbage collection & linktime optimization possible. With UEFI, dependencies are resolved at runtime so the compiler cannot know what code can be optimised out. With coreboot the linker is very good at throwing away code that will not be used. A reduced code size has many benefits:

- Faster execution time

- Reduced attack surface for vulnerability

- Faster compile times and therefore faster development

- Smaller binary size means a smaller flash can be used reducing BOM

To put some numbers on these claims let’s try to find a best apple to apple comparison out there: old 2011 Intel Sandy Bridge system. Those have 2 codepaths: a fully native coreboot codepath and also a binary codepath that is a wrapper around UEFI PEI(M) code. With native code the coreboot romstage is 87K large, which includes all the hardware init. Using the binary there is a 49K romstage + 191K UEFI PEI binary. With regards to build time, an anecdote from the AMD OpenSIL project will speak volumes. The AMD OpenSIL project has CI to buildtest its code in different host firmwares. At first there was only AMI APTIO-V being buildtested. That took CI roughly 20 - 30 minutes. When implementing coreboot CI, which supports exactly the same mainboard, AMD CI engineers were wondering what was wrong as it took only roughly 30 seconds to build a coreboot image even without any ccache.

TL;DR The UEFI implementation of hardware initialization is modularised. This increases complexity, code size, boot time. In comparison coreboot is simpler, smaller and faster while also achieving fully features hardware init.

Part 3: Development model and open source ecosystem

When comparing LinuxBoot and coreboot to UEFI there are 2 key technical differences that make the development model substantially different.

The first difference is that with both Linux and coreboot all code is developed in one tree or codebase. With Linux differences in hardware are abstracted in the driver code: e.g. you don’t have 1 driver per generation of GPU but a driver that thoughtfully captures similarities and differences between hardware generations. Coreboot has a similar approach to code, so that a lot of code is reused when a new generation of silicon is being released. This is to be contrasted with the UEFI model of development where for each generation and for each board the whole tree is copied and SoC and board specific modifications are made. The advantages of copying and modifying are that you don’t need to worry about breaking previous hardware or other boards. There is less need to collaborate with other developers. The one tree model however needs more overhead and collaboration, but has significant advantages:

- Maintenance across different boards and SoC is reduced. If an improvement, be it a fix or a feature, it is automatically available for all boards and hardware in the tree. There is no need to port a fix to all SoC or Board repos, just pull the latest master branch / release.

- The cost of deploying updates is reduced. As the codebase is the same for all boards, there is no need to validate non-board specific features individually.

- Because updates are cheaper, security fixes land in more timely (or even at all). With UEFI, you’re often left out of security updates.

- Time and cost of development is reduced: the board specific part of a coreboot port is very limited. Anecdotally some hardware vendors first do a coreboot port of their hardware to validate it, before porting UEFI, since it’s much simpler to get it working.

A second difference that contributes to differences in development is how modular UEFI is vs how monolithic Linux and coreboot is. UEFI consists of many PEI and DXE modules that can be separately compiled and put together. In fact Intel FSP, a binary which does hardware init on Intel hardware is just a collection of PEI and DXE modules. This modularity heavily favours closed source development. Every module can be separately developed and put together to generate a working image. It is commonly the case UEFI IBV (independant Bios Vendors) put in way more modules than is actually required to boot the platform. This is demonstrated by the NERF project (https://trmm.net/NERF/) that reduces the excess DXEs to use LinuxBoot. It is not uncommon to see completely wrong modules added to UEFI images, like Intel firmware components on AMD UEFI images. Also reinventing the wheel is a common problem with this overly modular architecture. Functionality from Baselib is commonly reimplemented for no good reason in modules. For instance on Intel Xeon-Sp UEFI code the hardware init has its own heap implementation alongside the common UEFI heap. With coreboot and Linux only one binary is created and upstream development is actively encouraged. Careless copying of code and duplication is usually blocked by the community driven review process.

Both coreboot and Linux are truly active upstream projects, maintained by a diverse and healthy community. To put in some numbers: at the time of writing coreboot has had 1202 contributors, Linux 26431, EDK2 531. Also when looking at the top 10 of contributors to coreboot we contributors ranging from independent developers, coresystems GmbH (gone), google, secunet, Intel, AMD, 9elements. On EDK2 8 out of 10 top contributors are from Intel, the other 2 are Red Hat and ARM. Having a healthy open community is probably the main argument why fully open source solutions should be pursued over closed source UEFI ones. Working upstream has its challenges mostly initially, as the code needs to reach certain standards and should not impede development of other platforms: collaboration has a certain overhead. However the benefit largely outweighs the costs: code quality is much better as this is required for collaboration on diverse platforms and use cases, code reuse is actively pursued to reduce maintenance costs, more eyes from diverse stakeholders make the code more flexible and secure. To develop firmware one needs to have a very solid knowledge of how the hardware works. This is a hard problem as hardware is incredibly complicated and is getting more complicated over time. Open source projects and communities optimise this sharing of knowledge. When asking a technical question on the respective fora, like bugtracker, irc, email, … of an open source project, one often gets a good answer quite quickly. This process is more efficient than for instance the ticket services that some silicon vendors set up to deal with firmware related problems, where a substantial portion of the time solving the issue is spent just to get in touch with someone that might adequately address it.

Along with these firmware specific differences there is also the generic argument for open source vs closed source like no vendor lock-in. You’re not bound to the company that delivers the software. This makes the market more competitive, but also holds future assurances as some companies might go out of business leaving you supportless.

Part 4: Does the OS need UEFI boottime and runtime services?

On x86 Linux does not need any UEFI boot time or runtime services, nor is any functionality lost when those are not provided. Linux can be given all the information it needs (ACPI/SMBIOS/E820/framebuffer) via other means. On other architectures like ARM64 the UEFI system table and some minimal runtime services are required. However this requirement is not the same as needing a fully fledged EDk2 UEFI implementation and very minimal implementations exist too, that provide as little as needed UEFI services. ARM LBBR fleshed out these minimum requirements into a spec.

Summary

Based on the facts presented in the article, it can be concluded that open source host firmware solutions like coreboot + LinuxBoot offer several advantages over closed source UEFI firmware.

In terms of performance and security, LinuxBoot and coreboot outperform UEFI DXE. The Linux kernel used in LinuxBoot is highly tested and under constant scrutiny, reducing the likelihood of encountering issues. Additionally, the use of Linux as the bootloader reduces development time and allows for more flexibility in writing applications, as Linux applications can be written in any modern language.

Moreover, LinuxBoot and coreboot result in faster boot times compared to UEFI, as the Linux boot process is better parallelized and has smarter dependency resolution. The reduced number of programs used in these solutions also makes maintenance of security updates more manageable.

From a development standpoint, LinuxBoot and coreboot offer simplified and more efficient development models. All code is developed in one tree or codebase, allowing for code reuse and reducing maintenance and validation efforts across different boards and systems. This also leads to faster development and deployment of updates. In contrast, UEFI requires copying and modifying the codebase for each generation and board, resulting in higher development and maintenance costs.

The monolithic runtime design of Linux and coreboot also provides advantages over the modular design of UEFI. The reduced code size of coreboot and the ability to optimize at build time result in faster execution time, reduced attack surface, and faster development. UEFI, on the other hand, often includes unnecessary modules, leading to larger and potentially more vulnerable firmware.

In conclusion, the comparison between UEFI and coreboot + LinuxBoot demonstrates that open source host firmware solutions offer better performance, security, and development models. The use of Linux as the bootloader, coupled with coreboot, simplifies the firmware process and provides more flexibility and efficiency. These advantages make open source solutions like coreboot + LinuxBoot a viable alternative to UEFI firmware.

Bibliography

- LinuxBoot Project. Available online: https://www.linuxboot.org (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- Coreboot Project. Available online: https://www.coreboot.org (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- "UEFI PI Specification 1.8". 2024. The Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) Forum. Available online: https://uefi.org (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- U-root Project. Available online: https://u-root.org (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- Intel FSP. Available online: https://www.intel.com/FSP (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- AMD OpenSIL Project. Available online: https://www.amd.com/OpenSIL (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- NERF Project. Available online: https://trmm.net/NERF/ (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- ARM LBBR. Available online: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/little-kernel-boot-loader (accessed on 2024-02-28).

- "Contributors statistics". 2024. EDK2, coreboot and Linux GitHub repositories. Available online: https://github.com (accessed on 2024-02-28).